In 2024, Monte Verde was ravaged by the worst fires in Bolivia’s history. The smoke was so dense that schools had to close, families were evacuated for weeks, and nearly 700,000 hectares of forest were lost. Thousands of people lost crops, livestock, and access to clean water.

When the air becomes so toxic that people must leave their homes for weeks, we are no longer talking just about natural disasters, but about a humanitarian crisis.

~ Javier Bejarano, Senior Technical Advisor at Forests of the World.

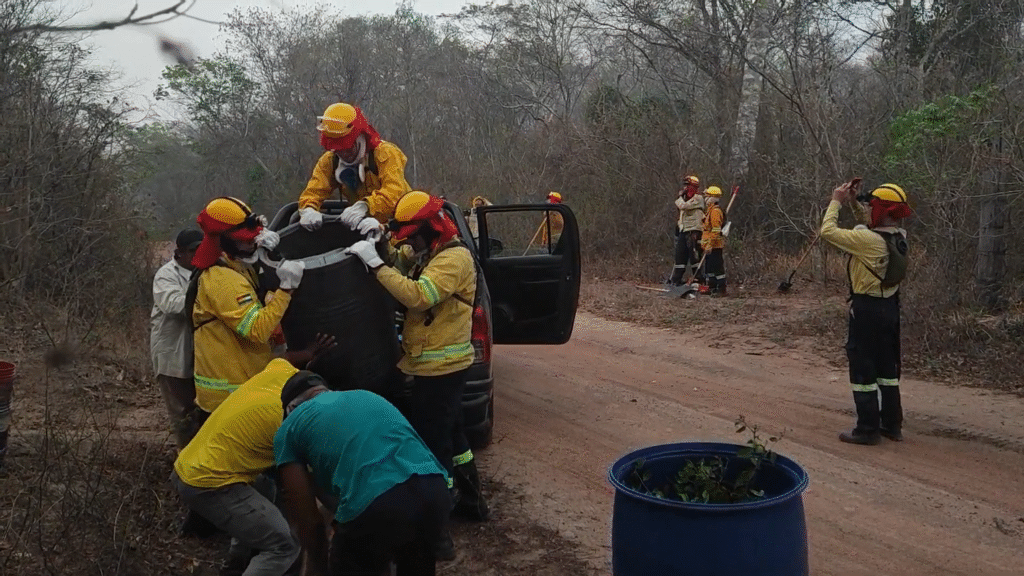

The strength of communal work

Monte Verde is an Indigenous Territory in eastern Bolivia, where communities have been working with nurseries, natural regeneration, and sustainable agroforestry systems since 2021.

They have formed community fire brigades, implemented local regulations for fire use, and established early warning systems.

Javier Bejarano highlights:

When the fires struck, it wasn’t the State, but the communities themselves, who were on the front lines. Their brigades and early warning systems saved lives, facilitated humanitarian aid, and reduced losses.

In total, 520 people were evacuated in a timely manner, and 1,608 families received food, medicine, and protective equipment.

Living among ashes

When the fire is out, the consequences for families aren’t measured only in charred logs.

The numbers may seem abstract. But behind the nearly 700,000 hectares destroyed in Monte Verde are families suddenly left without clean water or fields to harvest, and children who have missed months of school, explains Javier Bejarano.

For many, the smoke forced them to flee their homes for weeks; in 11 communities, schools were temporarily closed. Some families lost their livestock, others their entire farms. The production of cusi and copaibo oils, on which women largely depend, was halted for years. Losses are estimated at millions of bolivianos.

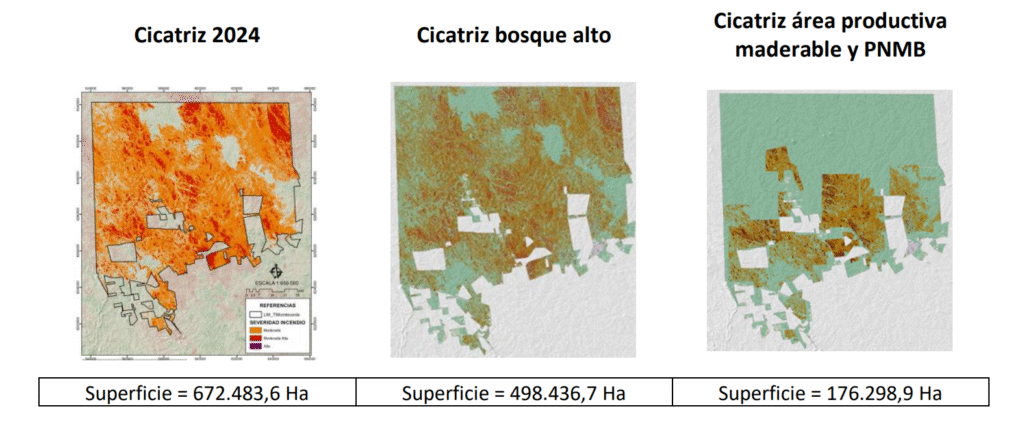

Satellite data from 2024 show that fires affected nearly 700,000 hectares (left, under “Cicatriz 2024” meaning “scar 2024”). Around 500,000 hectares were tall forest (center, under “Cicatriz bosque alto”), of which 176,000 hectares (right) were designated for sustainable harvesting of timber and non-timber products. These figures serve as the basis for calculating economic losses.

Restoring to resist

Of the 32,000 hectares under restoration in Monte Verde since 2021, two-thirds were destroyed by the 2024 fires. Javier Bejarano notes:

It may seem like years of work were lost. But satellite data shows that more than 16,000 hectares achieved denser vegetation cover and, therefore, were more resilient.

Agroforestry systems withstood the degraded soils better, and natural regeneration left green islands amid the ash. This confirms that community restoration is not just about planting trees, but about building resilience.

When we invest in local leadership, we don’t just create new forests. We build preparedness and response capacity, which is crucial when disaster strikes.

~ Javier Bejarano, Senior Technical Advisor at Forests of the World.

A global pattern

What happened in Monte Verde is not an isolated case, but rather part of a global pattern of record-breaking forest fires.

2024 was an extreme year: globally, fires were responsible for nearly half of forest loss, and Bolivia rose to second place in the world, behind only Brazil. Never before had so much tropical rainforest burned.

Global data shows Bolivia as one of the hardest-hit countries. Nearly 700,000 hectares were destroyed in Monte Verde alone, and more than 10 million hectares were lost nationwide.

It’s a clear sign that we face a systemic challenge, where both climate change and agricultural expansion are fueling the fires.

~ Javier Bejarano, Senior Technical Advisor at Forests of the World.

Climate change, drought, and El Niño create perfect conditions for wildfires that quickly spread out of control. When forests burn, they release enormous amounts of CO2, which further warms the climate and causes even worse fires. Scientists call this the climate-fire feedback loop.

The future depends on communities

Monte Verde demonstrates that community preparedness can make both people and forests more resilient. Communities saved lives, managed aid, and built forests that were more robust in the face of fire.

But the 2024 fires also made it clear that local efforts are not enough:

We cannot expect communities to bear this responsibility alone. They show the way, but political decisions and international support are essential to prevent this tragedy from happening again.

~ Javier Bejarano, Senior Technical Advisor at Forests of the World.

And there is a way forward. Strengthening communities and the leadership of Indigenous peoples is one of the most effective ways to prevent fires, protect biodiversity, and curb climate change.

When we invest in land rights, community brigades, early warning systems, and community-based solutions, resilience grows.

About Javier Bejarano

Javier Bejarano is a Senior Technical Advisor at Forests of the World and lives in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. He holds a degree in Forestry Engineering with a specialization in sustainable forest management from the Juan Misael Saracho Autonomous University. With more than three decades of experience in international development, capacity building, and sustainability and climate change projects, he has worked in strategic planning and program management, as well as supporting local communities on the front lines of the climate crisis.