La Prensa, founded in 1926 and a symbol of independent journalism in Nicaragua, was for many years one of the country’s most respected newspapers. Today, it is published only in digital format — from exile. Its offices were confiscated, its director imprisoned and later deported. Its journalists are now scattered across Costa Rica, Spain, the United States, and Mexico — but they continue to write.

In May 2025, La Prensa received the prestigious UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize. The very next day, the Nicaraguan government sent a letter to the organisation announcing its withdrawal. Not in protest against the prize itself, but against the recipient.

The government described the award as “a diabolical expression of anti-patriotic sentiment” and accused La Prensa of serving foreign interests. UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay warned that the decision would deprive the Nicaraguan people of important cooperation programmes in education and culture.

It’s not just about UNESCO — it’s about young people losing access to knowledge, culture, and a global community. It feels like the door to the world is closing.

~ Source who asked to remain anonymous for safety reasons.

The official withdrawal from UNESCO will take effect at the end of 2026. But this isn’t the first time Nicaragua has shut itself off from the international community.

A Pattern of Isolation

In February this year, Nicaragua also withdrew from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The decision came shortly after the release of a report showing that nearly one in five Nicaraguans lives with food insecurity — one of the highest rates in all of Central America.

The government dismissed the report as distorted and denied that it reflected reality. FAO, however, maintained that the analysis was based on independent sources and international standards. By withdrawing, Nicaragua loses access to technical assistance and food programmes — a heavy blow to the many families already struggling to make ends meet.

On paper, the country’s economy shows growth, driven by gold extraction and remittances from abroad. But as the FAO report points out, that growth is unevenly distributed. Poverty and hunger persist because resources fail to reach those who need them most:

While a few enrich themselves through gold mining, Indigenous Peoples pay the price — with polluted rivers, destroyed forests, and disregarded rights.

~ Anonymous source.

The isolation is felt not only in relation to the outside world. It is also felt within the country’s own borders, where freedom of expression has been gradually restricted, step by step.

Press Freedom in Exile

Since the mass protests of 2018 — in which, according to the UN, more than 300 people lost their lives — civil society in Nicaragua has been under constant pressure. Thousands of NGOs have been shut down, political opponents imprisoned or forced into exile, and press freedom has virtually disappeared.

When press freedom and civil society are weakened, the last spaces where people can be heard and find support disappear. The fight for rights becomes almost invisible.

~ Another source who asked to remain anonymous for safety reasons.

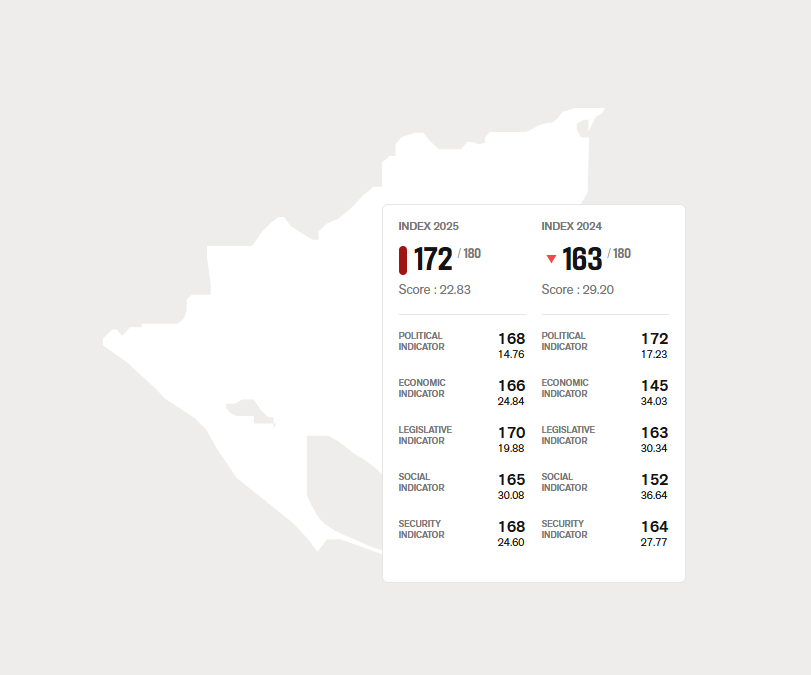

Today, almost the entire independent Nicaraguan press operates from abroad. According to Reporters Without Borders, more than 200 journalists have fled the country, and Nicaragua ranks 172nd out of 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index.

It’s not just organisations and media that are being shut down, it’s also critical voices, access to knowledge, and the possibility of international support.

Nature is paying the price, too

Nicaragua’s withdrawals from UNESCO and FAO are not merely symbolic acts. When a country removes itself from spaces where problems can be discussed and solutions developed, the consequences are tangible.

One of the most worrying examples is the loss of international support for areas such as the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve — the largest in Central America — which was recognised by UNESCO in 1997.

According to the latest report from Global Forest Watch, Nicaragua had the highest rate of primary rainforest loss in the world in 2024: 4.7%. Nearly 78% of this loss — amounting to 74,000 hectares — occurred in Bosawás. In just one year.

Without international cooperation and monitoring, protected areas like Bosawás become even more vulnerable to deforestation and resource extraction, which undermine both the environment and the rights of those who live there.

And while resources are extracted from the ground to enrich the few, it is Indigenous Peoples and their forests who pay the price. Mining, cattle ranching, and illegal logging are spreading unchecked. And with a silenced press, few are left to speak out.

What the government calls sovereignty, many experience as isolation, and perhaps even as a sense of being forgotten.

Even as the doors to dialogue close, one by one, the story goes on. It’s just becoming harder to tell.

Don’t forget about Nicaragua.

Sources

- UNESCO press release

- Reporters Without Borders – World Press Freedom Index

- FAO, UN Food and Agriculture Organization

- OHCHR 2019, United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

- Global Forest Watch Report 2024